A MATTER OF DEBATE

|

We are inching forward with our attempts to define this, in the expectation that it has been done dozens of times before, mainly by Welsh historians. Or has it? There is a great deal of debate in Welsh academic circles on the extent to which the media (including BBC Wales) does or does not accurately represent the Welsh narrative to the outside world. But hardly anybody actually gets round to defining what that is. Apologies to all of those whose opinions in print have been ignored -- there must be a great deal in the academic literature, to which I don't have access. All comments welcome!! Something like this? "Wales is a small country on the Celtic fringe of Europe with magnificent landscapes and rich natural resources. It is too close to England to have remained truly independent, and not far enough away for bloody rebellions ever to have taken hold. Throughout its history it has fought to resist the depredations of powerful neighbours; and against all the odds it has retained its language, its culture and its pride whilst encouraging toleration and liberal values and adapting to dramatic change. It has learned how to be subversive and seductive, and how to be spiritual and mischievous at the same time. In its history it has not suffered the same deep traumas as Scotland and Ireland. Its people are romantics, prone to wild swings of emotion; both melancholia and euphoria feature in the national psyche. Welsh people have a powerful "sense of place" and an abiding fondness for family histories, legends, ceremonial and ancient traditions. Eccentricity is embraced, while great value is placed upon learning. There is a tendency towards radical protest and an ever-present desire for social reform. Ultimately, Wales wants the respect of others -- and to be left in peace to enjoy and endure the ups and downs of the Welsh rugby team." Or something more poetic?

"Wales is two hours and a million miles away -- a small country on the Celtic fringe of Europe. The country’s green acres have seen a valiant struggle for self determination against a powerful and predatory neighbour. From the days of its ancient myths and native princes, to the ring of castles built by its conquerors, to its soaring rocky peaks and wild coasts, to its rich bardic and linguistic heritage, and the coal and iron that forged a global industrial revolution, Wales has always been a nation of tenacious survivors who have maintained a sort of stability in spite of millennia of dmatic change. Melancholia features large in the national psyche -- but so does euphoria, and the old mystics talked of two fighting dragons. Welsh people still have a powerful sense of place and an instinct for subversion and social justice. They still respect spirituality and have an abiding fondness for family histories, mysteries and legends, poetry and music, ceremonial and eccentric traditions. And in Wales you will find a living language, an open-hearted generosity of spirit, a real sense of mischief, and the warmest of welcomes."

The Steve Jones versionHere is anther "take" on the Welsh narrative -- it's very different to that explained by Michael Sheen in his 2017 lecture. Michael thought that Wales has always been a victim, exploited by a powerful and predatory neighbour -- and he also thought that we in Wales have been the victims of our own politeness, accommodating and adapting where full-blooded resistance might have been more appropriate. In this piece Steve Jones argues that we in Wales have never really been defeated or colonised by a powerful neighbour. The neighbour never was that strong, he says, but it has been very crafty, acting like a highwayman or a pirate to relieve Wales of its riches! In the way that we perceive Wales, there are many versions of the truth.......

|

A Log Line

This is the sort of thing that media people talk about, with reference to film or TV treatments. The essence of the story, in less than 50 words. So here is my attempt in just 30 words:

"Against all the odds, a small Celtic nation recovers from the depradations (some brutal, some subtle) of an immensely powerful neighbour, restores its self-esteem and retains its unique cultural identity." Jan Morris says:

Just a few quotes from Jan Morris’s book called “The Matter of Wales”:

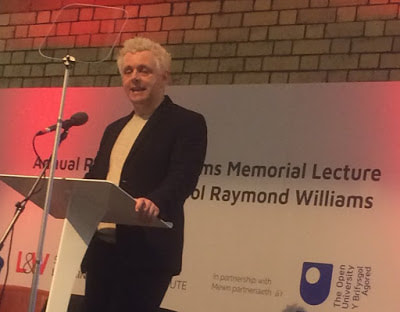

“.....it is a small country..... but its smallness is not pretty; on the contrary, it is profound. Intense and unaccommodating continuity is the essence of the place.......” “Its image is habitually blurred: partly by this geographical unfamiliarity, partly by the opaque and moody climate, partly by its own somewhat obfuscatory character, which is entrammelled in a dizzy repertoire of folklore, but most of all by historical circumstance.” “.... despite the overwhelming proximity of the English presence, a force which has affected the manners, thoughts and systems of half the world, for better or for worse Wales has not lost its Welshness.” “Among all the Roman possessions of the western empire, only Wales was never overrun by its heathen successors, and Welsh literature was the first in all Europe to emerge from the debacle.” “...... the Welsh came to see themselves as inheritors of Roman urbanity and Christian devotion, and as trustees of a lost Celtic civilization which was to become ever more marvellous in the imagination, peopled by ever more heroic heroes, inspired by saintlier saints, until the very dream of it became part of the whole world’s consciousness in the legendary paragon of King Arthur. Wales was the folk-memory of Europe!” “The Welsh never lost their sense of separateness and specialness, never allowed their language to die, and never altogether abandoned their perennial vision of a golden age, an age at once lost and still to come.....” “... if there is one constant to the Welsh feel of things it is a sense of what might-have-been, tinged sometimes with despair.” “Owain Glyndwr’s was a vision of the place as a human-entity, not just a country but a nation: not just a state but a fellowship, and a culture, and a heritage, and a sense of home, and a reconciliation of time, in which the affairs of the remotest past might overlap the present and embrace the future.” Michael Sheen enters the frayAll Welsh writers should settle down for a couple of hours and watch this lecture from Michael Sheen, on the subject of "Who speaks for Wales?" This was the annual Raymond Williams Memorial Lecture, given in Merthyr on Thursday evening. Some very profound and important points made by a brave man who freely admits that his celebrity status gives him license to say things that most politicians would avoid like the plague. Enjoy!

|

Narrative and Allegory

|

First, there was "Under Milk Wood" -- and then came "On Angel Mountain". The first was a work of undisputed genius. I hesitate to say the same about the second, since I wrote it, but I can at least seek to extol its virtues. If asked to summarise the content of eight hefty novels in around fifty words, this is what I would say:

A pregnant and suicidal teenager becomes Mistress of a struggling estate in the Wild West of Wales. She loses baby and husband, and with the help of assorted unlikely "angels" she refuses to conform or submit, fights for the rights of the downtrodden, and seeks to defeat the enemies who desire both her and her inheritance. That's the bare bones of it. If you want a slightly expanded version, how about this: In 1796 a pregnant, unmarried and suicidal teenager called Martha Morgan is plunged into a world of violence and corruption in the “Wild West” of Wales when she becomes Mistress of a ruinous small estate. She loses her baby and her husband. Somehow she survives, and with the help of assorted eccentric "angels" she tries to protect her family and her inheritance from prowling predators. She fights endlessly for the rights of the downtrodden. Over the course of 60 years, several love affairs and many involvements in the great events of the time, she becomes an incorrigible matriarch who outlives all of her enemies. At last she goes to her grave in a manner of her own choosing. She is, of course, Mother Wales, and her Plas Ingli estate is Wales itself . I have written many times about the symbolism built into the novels, and I have explained that I have tried to ensure that it does not become too obvious or too dominating. After all, if you are writing novels your prime duty to the reader is to entertain by telling a good story in a competent way. So the mountain, the house, the raven, the cave, the spring, and even the kitchen table are there in every single novel, recognized as symbols by some readers but not by others. They resonate and tell us that there may be more going on than meets the eye. The symbols also reinforce for the reader the idea that Martha is not just a small woman caught up in petty events but is a seriously important literary figure who has something to say about the human condition generally, and more particularly about the role of women in society. For me, she is still endlessly fascinating, although I am still uncertain how she evolved and why she turned out to be herself a symbol. Mother Wales. That term was first used by a Scottish friend who read the books, and it has been used by many other readers since then. And although it was never my intention to create a character worthy of that title, in retrospect I now see that while I was doing the writing, one novel after another, that character was slowly emerging. So yes -- Mother Wales, just as we have Britannia, Mother Earth, Mother Nature, The Earth Goddess, and the Eternal Idol. In myths and legends from across the world, powerful and even fearsome women pop up all the time, as they do in literature. And these female / matriarchal symbols are idealised not just as gentle mother figures but also as figures who have weaknesses and even tragic defects. So the goddess becomes lover, sorceress, temptress and witch -- and she is capable of jealousy, lust, rage, and a multitude of other vices. That's Mistress Martha all over....... So if Martha, who is very far from being the "ideal heroine" or "perfect woman", somehow represents the protective spirit of Wales and is referred to by readers as Mother Wales, what about her relationship with the land? Again I did not consciously work at this, but it seemed to me entirely natural that Martha should have a profound and sensuous relationship with her patch of land, her mountain of Carningli and her little estate of Plas Ingli. So the mountain is her cathedral -- she reveres it and even worships it. She feels that she is part of the mountain and that the mountain is a part of her. When -- for whatever reason, she is away from the mountain and the Plas, her sense of hiraeth becomes almost unbearable. The intensity of the relationship between person and place is not uniquely Welsh, since it exists also in many other countries in rural communities in particular. But in Ireland and Scotland, the love of the land is tinged with sadness and anger arising from the Clearances and the Great Hunger -- with resistance, revolution and armed conflict running right through to the present day. The relationship with the land has both love and hate in it. In England the love of the land has been diluted by industrialisation, urbanisation and "modernisation". In Wales it is still there, with a mystical and romantic component which makes it very special..... Back to the log line and the enemies -- the prowling predators -- who have designs not just upon Martha herself but on her little estate. Her little patch of land is rough, and not particularly productive, but it is immensely beautiful, and it has the history and the traditions of an old family embedded in it. It is surrounded by larger and more powerful estates owned by predatory members of the minor gentry who see it as an inconvenience and even as an irritant -- especially since, under Martha's guidance it becomes a place of compassion where equality and tolerance are promoted and where a variety of social experiments turn labourers and servants into friends. On the Plas Ingli estate social barriers are broken down and the inhabitants get occasional glimpses of something that is not quite utopia, but is at least a little better than the miserably that afflicted many parts of early nineteenth century Britain. Those who become Martha's friends are the angels who protect her whenever she gets into trouble -- as she does, all too often. Predatory neighbours with expansionist intentions and an instinct for suppression and exploitation? Now where have we heard that before? So if you were to ask me whether, in the stories of the saga, the Plas Ingli estate is really a symbol for the nation and the rough green acres of Wales, I would reply in the affirmative. If that makes the whole saga an allegory, so be it. Like Animal Farm, The Lord of the Rings, Pilgrim's Progress, or The Werckmeister Harmonies? That's fine by me. |